Tariffs, Ideology, Complex Systems (a bit of a rant)

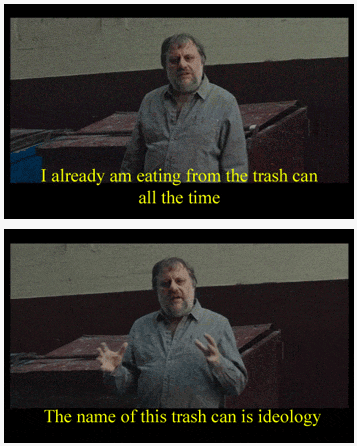

Long time no post. I think between the last time I used this blog instead of my day job(s) to write the actual book Building a Ruin came out. You should buy it. I have returned because I have meant to write in this format again for a long time, and because I can't think of a better format than a blog post to try to wrap my head around what is happening with well... everything. More specifically, I will discuss the tariffs and their impact. There is so much to say, and frankly, I also need to think about why people with whom I agree on very fundamental core problems, the problems of global monetary architecture, and consider my mentors and teachers, are even giving credence to this. As part of this introspection, I am putting on my best Eastern European accent, grabbing two hot dogs, and discussing ideology, or at least how we construct narratives of meaning to make sense of the complex systems that undergird capitalism. In other words, a lot of political economy is how we use economic ideas and concepts to create a language of politics that makes sense and papers over the inherent tradeoffs of living with a complex system that has a logic but no agency. I get into this quite a bit in my book, and a long-suffering follow-up planned methodological article that I, too, can't figure out how to build a neat narrative around. All that said, I think ideology isn't false consciousness but how we construct the routines and political categories that make sense to our coalition, despite all of us having some minor or significant disagreements underneath this shared vocabulary. There are a few responses to the impact of the tariffs that are doing this in one way or another.

The first is one I would call a personification narrative, which tries to find some rational agency in the movement of asset prices and trade flows. At its most extreme, it wants to vulgarly politicize the workings of a complex system of feedback loops that is the capitalist economy and its plumbing into a story of individual decision makers pursuing a coherent agenda rather than examining a system as well, a system. I see this one as something that exists both in Trumpian discourse and in responses from well-meaning but ultimately incorrect people.

On the Trump side, you have a narrative that US trade deficits result from countries and their leaders "cheating" and intentionally taking advantage of the United States. The flip side of this is that the US needs its own cheater-in-chief to even the playing field, aka Donald Trump (note that Trump always says it's not that they are bad people and that if he were in their shoes, he'd do the same thing). Of course, this is nonsense. Rarely are countries positioning their macroeconomic policies in a way that explicitly targets another. Instead, like all of us, they make pretty short-term decisions, guided by internal logic and constraints. In the case of persistent trade surpluses, they are often the flip side of building up FX – mostly dollar-denominated – reserves, which you want to have around as insurance in case you have a run on your financial system. Most transactions are denominated in dollars, so all countries have some degree of exposure to US dollar liquidity risk. They will rationally tend toward a policy that accumulates highly liquid US dollar-denominated assets, mainly US government debt, to preserve their monetary sovereignty. To buy dollar assets, you need dollar receipts, so you want to run a trade surplus. They aren't getting a good deal out of this if you ask them (now watch me slip into personification because it's a good deal for some people and a bad deal for others, no matter where you are sitting in this hierarchy). And as many, including myself, have argued, the US also suffers some downsides because it has to play the role of the hegemon, providing liquidity to the dollar system, and that also comes with tradeoffs. All this is to say that this is a complex coordination problem that can't be solved by some people around a table, and even when it is, it's never an optimal solution: it's give and take. The consequences are not suitable for everyone, but they can be managed as consequences of a systemic logic rather than specific intent.

I will get back to the Trump narrative later on, but I think there is a very similar, if not as structured, thing going on with the discourse on the adverse market reaction to the tariffs. One is a "bond vigilante" argument involving some market actors or even individuals punishing Trump by selling treasuries and driving up yields. The market and its participants are presented as some arbiters of morality, presenting Trump with the consequences of his actions. The most absurd story is about Mark Carney and the Japanese government working together to dump bonds to punish Trump. Not only is there no evidence of this, but it's implausible given that Canada doesn't hold that many treasuries.

I suspect some of this comes from the folk wisdom that equities and treasuries move in opposite directions since turbulence in risky assets like stocks moves people to less risky assets like US debt. In turn, the message I saw in my social media feed was that other countries were losing faith in the US dollar and that financial Armageddon would soon come as just punishment.

The problem is that the folk wisdom is just half right. Treasuries are safe because they are cash-like – in other words, you can easily sell them for cash to pay off your debts in a crunch. Given the dollar's centrality in global transactions and how relatively cheap it is to swap into any other currency, holding treasuries makes sense if you need to bank a lot of money no matter what your nationality (though an overwhelming amount is owned by US domiciled entities the top by far being the US government itself). It also means treasuries are a great form of collateral if you want to borrow money on a short-term basis to make a risky investment. Like all money market products, there is also speculation on treasury rates. This comes together because when equity prices fell, there was a rush for margin, aka cash, and to get that cash, many entities had to liquidate their bond positions at a worse price. It didn't help that hedge funds were playing with regulatory and basis trades that bet on the spread between present and expected future prices of treasuries.

Where the folk wisdom goes wrong is that what makes treasuries so money-like is that everyone knows that, in a real crisis, the Fed will make the market and buy them. However, unlike most crunches in treasury liquidity driven by a big macro event, this one was not just deflationary but also inflationary. So, the rate at which the Fed will market itself will be quite a bit higher. Thus, the yields are blowing up pricing in both weak economic growth and at least temporarily high prices. It is the feedback loops of complex market structures at work and a confirmation of the centrality of the US financial markets.

I promised to return to Trump's political positions and stories vis-à-vis tariffs. They are crude and factually wrong, but I am surprised by their consistency. The narrative you hear from Trump himself is that tariffs are how he will solve the trilemma of a balanced federal budget, low tax rates, and high employment. He's saying that tariffs will somehow replace income taxes and stimulate jobs. It's a potentially compelling political narrative for him because it helps unite what he sees as his core coalition: it offers a way for small government conservatives, plutocrats, and male blue collar workers to all get what they want, papering over their differences.

It's a bold strategy, but it has some problems that I suspect Trump even understands on a gut level. The consequence of such a policy will be that either inflation is very high, and/or that rates will be very high, and outside his base, that's what people voted against when they voted for him. So somehow Trump has to brute force rates lower and hope no one notices inflation. Enter the so-called "Mar-a-Lago Accord." It's a pipe dream that Trump, using his skill as a negotiator and tariffs as leverage, will force the rest of the world to refinance their holdings of US debt with interest-free 100-year bonds. In theory, this would reduce the US budget deficit because the US spends most of its federal budget on interest payments and, by default, drive down the interest rate. Of course, most of that payment is to domestic entities and social security, so it would make little difference.

This, again, is an ideological statement more than a real plan to reform and restructure a complex system. First, it is retreating into the exact kind of personification of market structures that I described above, posing Trump as finally hitting back against a conspiracy of foreigners. Instead, it just doesn't reconcile with why the outcomes of the system are what they are, which is that treasuries are other people's bank accounts, and turning them into perpetuities means they lose their usefulness. Moreover, how would other countries pay for these? Would the US accept foreign currency for them? No, of course not, they'll demand dollars, and how does one access dollars if one does not have access to the American money printer? Well, it has to get them from someone else who can at least guarantee more dollar-like instruments on demand and thus, eventually, a US counterparty. In other words, you would need to continue to have trade imbalances. Without those, the entire scheme falls into itself since it will reduce the purchasing power of US consumers as things become more scarce, aka inflation. The only way out is maybe the final piece of the Trumpian discourse: magic venture capital-led automation that somehow boosts productivity while simultaneously destroying all jobs and maintaining manly blue-collar work.

And this won't just hit the US. As it becomes harder to finance trade and capital assets, it's more likely that trade and growth everywhere slow down rather than everyone adjusting to some new standard arrangement. So rather than a grand displacement of a reserve currency, we'll slowly ride down Kindleberger's spiral to a poorer, more fragmented world. The results won't be pretty, but they will be slow and grinding. Instead of a grand deliverance of justice on the US for electing Trump and breaking a system it derives enormous benefits from, everyone will be dragged down together. Justice doesn't work that neatly.

It would be easy to assign malice to this nonsense, and there is a degree of it. There is also indeed self-interest on behalf of the oligarchs backing Trump, who might still hope they can get their tax cuts while holding onto Trump's populism (though I suspect they realize their losses aren't worth it). However, Trump isn't doing something that every political movement does in one way or another. He's trying to create a narrative and set of common reference points that transform issues associated with complex systems into digestible ones with easy solutions. To give him his credit, that's his greatest talent. The man is a master ideologist in a world where ideologies have fewer stable reference points in "big ideas." However, I suspect that the contradictions and unexpected consequences of trying to take as complex a system as global trade and payment out of homeostasis with blunt tools will create feedback loops that even he can't paper over.