Public Options as Industrial Policy

Ezra Klein published a column calling for a "liberalism that builds." More specifically, he endorsed Brian Deese's invocation of "industrial policy" to "expand productive capacity beyond what the market, on its own, would support." I am very heartened by this. Klein is a barometer for polite Washington D.C. discourse and for a very long time the words "industrial policy" would get you tossed out of it.

But as happy as I am to have my pet issue become much more salient, I am very concerned by how pundits like Klein are discussing a "supply-side progressivism." Klein identifies two blocking coalitions. First, these mainstream liberal appeals rely on "innovation" as the main justification for industrial policy. The idea here, which is correct, is that new technologies are too immature for the market to install successfully so they need government support. However, we are actually quite good at innovation in the United States. We aren't very good at production and installation.

Second, they argue about government efficiency. Again, there is a lot of truth here. Procedural liberalism is hurting the ability of the government to be flexible in setting the supply side of the economy and it might actually put democracy itself in danger. Klein cites right-wing knee-jerk anti-statism and a liberal deference to multiple interest groups as hindering the capacity to build. Once again, this isn't wrong.

However, I think the problem is deeper. Our economy has become terrible at managing fixed assets and capital investment. This might sound crazy. The US is a very deeply developed capitalist economy with the world's deepest financial market. Of course, it should manage these tasks well. However, if we look back at the past 30 years, the American economy is actually very "asset-lite." American firms have tried their best to avoid capital investment. This feeds back into state capacity. Running an economy with lots of fixed assets creates know-how.

The issue of capacity then is how to move our economy from a capital-lite to a capital-intensive system. That entails a problem because capital-heavy systems are just as unstable and inflationary as the current system. If we are serious about industrial policy, we must confront the market's limits to generate the stability needed to sustain investment into fixed capital. That means that our first priority should be creating public options for capital-intensive goods.

This is somewhat at odds with the emerging conventional wisdom. The hard part of industrial policy is not going to be investing in leading-edge technologies. We know how to do that quite well. It is going to be to create the value chains that support those leading-edge technologies including raw materials, manufacturing, housing, and energy supply. These are all capital-intensive activities in which the state needs to buttress the market beyond the initial stages of installation. To get our minds around that we need to go understand the process of investing in fixed capital goods.

The Instability of Capital Investment

At its core, industrial policy is about fostering investment into capital goods and the labor force needed to operate them toward some goal. The easiest way to think about capital goods from my point of view is to see them as a kind of bond. A bond is just a credit instrument that an entity markets which says for paying me some amount of money upfront, I will pay you a regular stream of payments over time and return the principal at some date. A bond is just a loan floated on a market instead of dealt through a bank balance sheet.

Let's apply the same logic to a machine that makes widgets. I get a loan or issue a bond to finance that machine's upfront cost. That covers my upfront costs (we'll assume no labor here for simplicity) and now I am making widgets. My widgets are selling like gangbusters. However, part of my receipts for the sale are going back to the lender as "quasi-rents." Meanwhile, the machine has wear and tear that reduces its present, upfront value, aka its principle: depreciation. All together, we can see how a capital asset – the widget-o-matic – is actually a creature of financial calculus and cash flow.

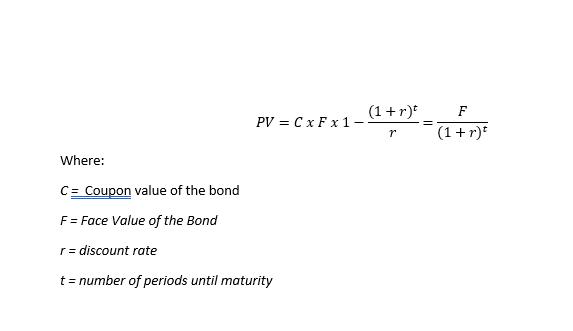

Now that we are clear about the relevance of bonds to understanding capital we should also understand how bonds are valued. The basic bond valuation formula is:

First we calculate the present value of interest payments:

Note the term r. That is the interest rate usually set by some reference rate like a US treasury bond. Thus, bonds are rate sensitive. If the interest rate rises, then it isn't as worth it for an investor to invest in a risky bond paying some coupon that is lower than the rate that she can get just by sitting in cash in a bank deposit. Something similar comes into play with capital goods. A capital good has a rate of return that is determined by the price of its current output and an expected rate of return on future output.

Borrowing Keynes' terms, Hyman Minsky describes the first price as the "demand price" for current output that is set via short-run factors including current demand and overhead costs for labor, and a second "supply price" for capital goods, which is the cost for investing in installing the capital good. The distinction is that the former is the consumer good – in our case the widget – and the latter is the widget-o-matic.

Where things get tricky is that the price of the widget in the future has to justify the price of investment into the widget-o-matic now. That means that a firm has to take into account the repayment of the quasi-rent in its pricing decisions. Moreover, in the real world, my widget company is the customer of the widget-o-matic company and they have to cover their overheads too. They have workers who need wages that cover the costs of buying widgets for me. So their wage will have to cover the increasing cost of widgets and other goods that are produced due to investment.

Minsky's more famous financial instability thesis actually emerges out of his insight into the process of investment. Funding for new investments starts with players who have good steady balance sheets and then progresses to Ponzi finance where the need for return outstrips the demand for goods. From there, you get Minsky's famous "financial instability hypothesis" and a debt deflation-driven crash if demand is not restored or inflation if we have an upward swing in prices due to firms using structural advantages like monopoly power to increase markups. More on this below.

Another way to look at the problem of capital formation is through reference to the even versus uneven development debate in development economics. Theories of "balanced growth" argued that the stability of growth required multiple sectors to be developed at once. For example, Ragnar Nurske argued that a developing country should invest both in agricultural and industrial sectors so that one would form a market for the other. By contrast, unbalanced development theorists like Albert Hirschman believed that it was too much to ask for a developing government to facilitate growth in multiple sectors. Instead, development needed to create the very disequilibria that balanced growth theorists feared would destabilize a developing economy. Investment in leading industrial sectors would create backward linkages that could stimulate the development of supporting industries and forward linkages that would incentivize more production further up the value chain. "Last industries" – or industries that transformed raw materials and intermediate inputs into final demand – are particularly important since they create the most backward linkages.

Hirschman and Minsky together can tell us a story about how to understand industrial policy as a set of dynamics in both supply and demand. Minksy's cyclical approach to capital formation has two extremely powerful implications. First, the leading role of demand in the schema points to distribution as a driver of growth. Second, it flips conventional economic models upside down. In Minsky and Keynes' world, money is not neutral. Financial decisions, the expectations of cash flows, and the need to settle debts drive the real economy rather than the other way around. This implies that capitalist growth is unstable and that markets do not always allocate resources efficiently. Minsky is famous for being a scholar of financial bubbles but those bubbles are connected to the real economy through the process of capital investment.

Stabilizing an Unstable Industrial Policy

There are two ways in which one can embrace the policy implications of Minsky's investment process. One is a cautious manner, reminiscent of even development, where we try to tame the animal spirits of the financial markets. Minksy himself was probably in this camp. Minsky argued that the increasingly high profits necessary to sustain a high investment economy required ever-higher markups. As the volume of investment into highly capital-intensive intermediate goods increased due to financial exuberance, workers would be competing for a gradually falling supply of the same consumption goods. This would drive up wage demands and force higher markups, thereby causing inflation.

This is why Minsky thinks a high investment economy is inherently inflationary. To stem this cycle, the central bank raises the interest rate – r in the equation above – so as to make the current price of future commitments – the supply price – far higher than the current demand price thereby slowing investment. However, the reality of the matter is that it does this not through some cost of capital which is highly diffuse but through the creation of unemployment. People who are out of work don't plan on consuming in the future. There are two alternatives to this mess. One is Minsky's recommendation of an economy focused on consumer goods that are produced by labor-intensive means and anchored by a government jobs guarantee. Minsky is thus more sympathetic to Nurske and balanced growth theorists.

The other is to emphasize the influence of Minsky's teacher, Joseph Schumpeter. As I alluded to above, there is a whole school of "neo-Schumpeterian" theorists who combine Minsky's insights with Schumpeter's. Scholars like Carlotta Perez, Bill Janeway, and Mariana Mazzucatto all, to some extent, agree that financial speculation is necessary for the deployment and installation of new technology. The problem is not "the bubble" but the "bailout." The bubble is a natural part of capitalism but the bailout needs to be designed to help mitigate the consequences of the bubble for working people, spread the newly installed capital to a wide range of firms and households, and get the public which usually funds long-term innovation a return on its investment. Janeway explicitly distinguishes between productive and unproductive bubbles. Neo-Schumpeterians can be compared to Hirschman and unbalanced growth theorists.

There is a middle way between these two poles. Stabilizing the instability of the investment process means focusing not just on the backward links from the innovative sectors but on their place in industrial linkages. Innovation in customer-facing industries, for example, is actually easier. Last industries generally have more customers with a greater variety of personal budgets and propensities to consume. Thus, the demand cost of these industries can be relatively stable and supply costs will respond to aggregate demand more quickly. However, raw materials and intermediate goods industries don't share these features. Profits are less stable since these sectors have fewer buyers and demand shocks are transmitted more unevenly. They also usually require a lot more fixed capital thereby creating more instability in their firm's balance sheets. This links our Minksy problem to my previous discussion of Adolph Lowe – how to move resources into those more volatile sectors to match the needs of consumer demand? In other words, how do we clear bottleneck sectors?

There are several historical examples of these types of policies working. Recent research by Nathan Lane on the successes of Korean industrial policy finds that it was successful because it built forward linkages from intermediate sectors to last industries. Korean industrial policy worked better when the state invested in industries that could support other industries closer that were high profit and closer to the consumer market. State support was vital for capital formation in high capital cost, lower profit intermediate goods industries. This lowered the price of inputs for the more competitive and profitable industries closer to sources of demand.

Another example is the use of Marshall Plan funds in West Germany. The popular image of the Marshall Plan is that of a giant American investment into European industrial infrastructure. This is a myth. Marshall funds were not very big. The majority of the plan's impact was to coordinate the re-establishment of inter-European trade and re-set Germany as Europe's industrial heartland. But there were instances where Marshall funds had a huge effect – counterparty funds set up in Germany's state development bank – KfW. Germany pledged to match Marshall funding and set up a development bank to run a revolving fund. Most importantly, these funds did not go to Volkswagen or other industrial giants. They did go into building housing for refugees and miners who needed to be relocated due to the shock of the war, securing raw materials for the clothing industry, and restarting the electricity sector. These were all capital-starved, low-profit bottleneck industries requiring high amounts of capital investment. In doing so, it facilitated higher profit industries to have a stable markup for their inputs and thus created steady growth.

We should approach industrial policy as a public option for fixed capital investment. The goal of that investment should be to absorb uncertainty in the state's balance sheet, where it is most bearable. Neo-Schumpetrians are correct in stating that uncertainty is very high at the end of the innovative process – where technology is not yet known. However, there are other places that we need to invest in that are less sexy because of the uncertainty embedded in the investment process– bottleneck industries which are high investment and producer-oriented sectors such as raw materials, intermediate goods, energy, and housing. Though they are not always cutting edge, these sectors have a long payoff for investment which means that Minsky's supply and demand prices for capital can easily find themselves out of equilibrium. Because of this, price changes in these sectors can be extremely volatile and feed into directly consumer-oriented sectors. Thus we need an economy where there is an engine pulling us forward but also well-maintained rails for that engine to run on. We need to make sure that upgrades to the engine don't crush rails laid in an earlier time. That will take public investment into bottleneck industries to build resilience. It also opens up a new paradigm

Industrial Policy in an Uncertain World

I want to return to the Klein column that started this post. In it, there is a critique of government efficiency in responding quickly due to overly onerous regulation. While that might be true, there is a larger problem in doing industrial policy in industrialized economies – what is its goal? In industrial policy's heyday it was largely seen as a means of catching up in development to some frontier. However, I think it needs to be redefined for a technologically advanced, innovative economy like the United States. The goal of industrial policy should not be to catch up. Rather it should be to create stability in the investment process. That might mean a very different kind of measure of efficiency that Klein and the authors he mentions believe in. It might mean more focus on redundancies that make sure that for-profit markets can function well.

This means that the government should not necessarily be a project manager at Google. However, it might want to fund the cutting-edge research that leads to a Google through public incubators. However, it should also make sure that the service employees that clean Google's offices have housing and public transit – far more capital-intensive goods. Beyond these usual functions, we should also make sure that electric cars have enough lithium to power their batteries. While private investment is ramping up into lithium mining, it is slower than the pace needed to ensure battery supply. The results of this will be both higher prices and a rash of environmental and human rights violations as market actors rush in to extract goods quickly.

There is a final point I want to make here regarding the politics that underpin a lot of industrial policy. One reason that we could avoid these discussions for decades is that the world was increasingly globalized. Outsourcing production allowed for many low-margin goods to be produced using cheap labor through labor-intensive processes. The Keynes-Minsky position would be that this is disinflationary because it reduces the need for expensive capital investment. In some manner, the world we got during neoliberal globalization was a nightmare version of the low-investment developed economy that Minsky advocated to cure the inflation of the 1970s. Yet the costs of this fell onto working people via unemployment and low wage growth.

Our economy is a sports car. It is nimble, light, exclusive, and fragile. It can only work if we have the smooth roads of financial globalization. That time appears to be over. We are not going to have the smooth roads that enabled a nimble capital-light, private investment-driven economy to prosper. We did not do enough to maintain those roads, which has led to a situation where roads are literally being shelled by the enemies of democracy. We are reaching the point where we need to realize that we will have some elements of what Perry Merhling has called a "war finance" – more state-directed resources – if liberal democracy is to survive. It's past time to trade in the Ferraris of the great moderation for the Ford F-150 Lightening we need to cross some rocky ground.