What Makes an EM?

Hi Readers,

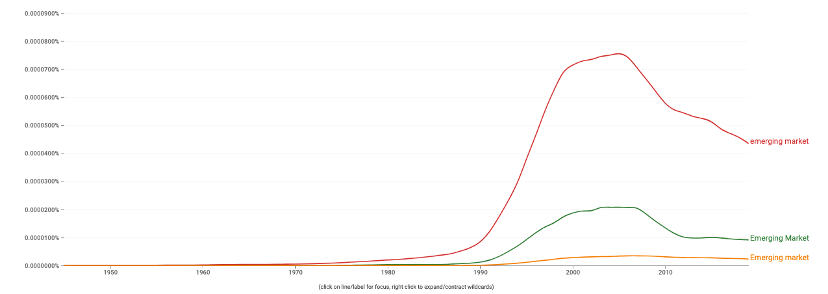

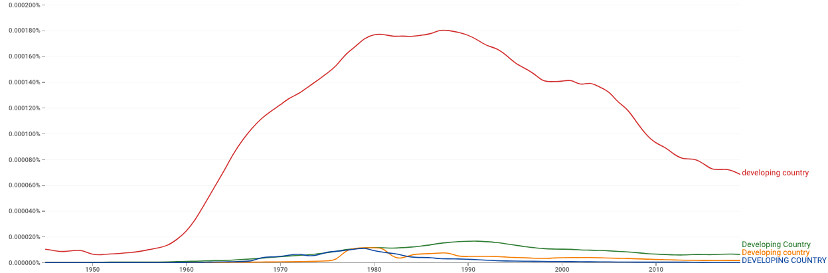

As some of you know, I teach a course on economic policies in emerging markets at Tufts' GBA program. I like this course and am slowly but surely making it my own, editing the readings and lecture setups. I open the classes by asking students to define an EM and how it differs from a DM. Of course, there are many definitions. One of the reasons for that is that the term "EM" is pretty new. It emerged (pun intended) in the 1980s as we began to see the issue of "development" go away.

Disillusionment with modernization theory and industrialization created new ways to think about economic hierarchy. For example, instead of industrialization, international organizations and governments began to consider poverty alleviation and covering "basic needs." The driver of growth moved from policy to the private sector. From there, you get your microloans, ext.

However, the problem of development has not gone away. We just do not talk about it. When commentators talk about successful development by middle-income states, they still talk about moving up a value chain. The classical Lewis two-sector model in which the goal of an emerging market (and I would argue ANY economy if it isn't run by rentiers and capitalists who are bad at their jobs) is to move its labor force from low productivity to higher productivity activity and therefore increase the surplus and, ideally, well-being. As I discussed in my previous posts, some methods to reach middle-income status seem to work. All of these methods, in one way or another, deal with Gershchenkron and catch up growth. The key problem remains how to get inputs, which need to be imported.

In the days of modernization theory, we could talk about development as some movement toward industrial modernity and build targets from that end goal, then try to figure out what inputs human, and non-human, you needed to get to that end goal. That was what was called "development planning." Now that we have rejected industrial modernity as a metric for development and a form of social organization, we have nothing to plan for.

Instead, we think of EMs as specific kinds of markets in a world of mobile capital. Assuming this ontology, the definition of EM vis a vis DM is one I will borrow from my friend Karthik Sankaran "an EM is a credit risk, and a DM is an interest rate risk." In other words, an EM can't control its debt because it needs to finance in someone else's money, and a DM can't control its interest rate because it has offloaded that to a central bank. In turn, the DM can't use a lot of the same intervention tools in the real economy because the Kindleberger dilemma means that to make its money extra receivable – aka you can generally buy anything you want in it no matter where it is – you have to give up control over your capital account. Thus, you are left only with the feedback loop of the independent central bank as your economic policy tool outside some demand-side interventions. And as such, your obligations should be understood as having an interest rate risk.

In global capitalism, no one is sovereign unless you do something to make yourself free. That's not a pessimistic outcome. It just means that you have to understand where you are in the hierarchy of money and the tradeoffs that come with it. Then you design policy accordingly. The persistent trade surpluses you see from many EMs are one adaptation to this reality. They are a form of self-insurance. Nothing wrong with that unless you are a worker in one of those countries and the nominal gains from development are beginning to run up against the real losses on your consumption. It's a solution, albeit an imperfect one.

For DMs, we also have solutions – outsourcing, just in time, NAIRU, ext. These are based on repressing the labor share. As a result, we have a productivity problem. A lower labor share does not encourage installing labor-saving technologies. Instead, entrepreneurs focus on getting more pieces of a slowly growing market.

Great system we got there...

Most of my intellectual work lately is to devise a form of development planning that does not have some fixed end goal and can be flexible and adaptable to multiple monetary circumstances.

All that said, here are the slides I use, to sum up the entire set of problems from the POV of an EM. There will be many familiar things here from my teacher, Perry Mehrling's, money view.

This is a deeply sad and personal post since it is academia rejection season, and I am now fully to grips with the fact that I will never be part of the historian's club. That's ok. I love teaching when I can. If any of my students, past or present, are reading this, you are all great. Typos my own, ext.