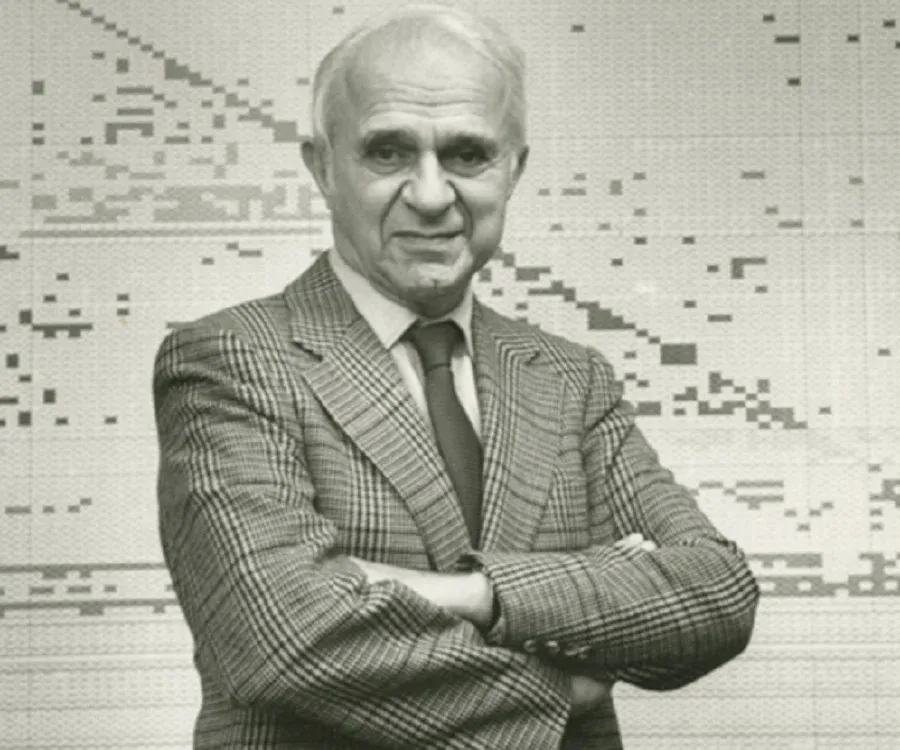

Economists We'll Be Talking About: Wassily Leontief

My theory of how economics interacts with policy is a bit more complicated than some more popular accounts. Very good studies on the anthropology of economics as a profession and policy-making discipline. For example, Marion Fourcade, and Elizabeth Popp Berman's work, have noted that economics' political influence and professional formation are deeply embedded in particular differences in local political cultures. Thus, for example, I think that in the United States, lawyers tend to be very important transmitters of economic ideas into policy. American policymakers tend, themselves, to be lawyers, and the government itself has deep legal performativity, even in the bureaucracies.

Despite these longer structural patterns, in the past few decades, I think there has been a bit of technological disruption in how economics and economic ideas move into action. A few years ago, I coined the term "posting to policy pipeline" to describe how the econ blogosphere and Twitter have become key sites of idea making. Before the advent of these new forums, the top economic journals really dominated everything and painted the conventional wisdom as having some scientific validity. After the advent of social media, one could not only call Larry Summers an idiot to his face without being invited to an exclusive meeting but also explain to a large audience precisely why he was an idiot.

Like all technical changes, the emergence of the posting-to-policy pipeline had a strong social component. In the wake of the 2008 crisis and the great recession, a whole cohort of people became interested in the economy who would never would have entered the field before. In the late 1980s and 1990s, economics seemed a "settled" discipline from the outside and associated, fairly or not, with free market dogma. After 2008, younger scholars who would have reason to be critical of such dogma rediscovered economics and economic thought more broadly. I think this effect created not only a cohort that was ready to act when the COVID crisis came but re-invigorated some traditions in economic literature. In particular, macroeconomics was reborn in a more directly Keynesian tone. In the wake of 2008, we all began re-reading Keynes and his more radical counterpart, Kalecki, as a primary source, not just a modeling tradition. What we discovered was that what was called Keynesian macro had little to do with the economics of Keynes.

Like an underground stream that bursts through the surface, the Keynesian revival really gained traction after the 2016 election of Trump, as even mainstream thinkers began to accept that the Obama recovery had gone horribly wrong and searched for a grounded, implementable agenda. Keynes had his moment. Zach Carter's biography of Keynes, The Price of Peace, capped this moment. Unlike the biographies that came earlier, it really was a political biography of a thinker and the ways his ideas were used and misused. The fact that it became a New York Times bestseller is not only a testament to Carter's ability as a writer but to the moment.

In my opinion, we are past the Keynesian moment. Not because Keynes is not relevant but because we are entering a moment with a slightly different set of problems. Keynesian macro will remain very relevant, but in the age of big fiscal spending and climate-driven industrial policy, we'll need some more "micro" thinking. In the early 1990s, Jan Kregel contrasted "offensive Keynesianism," or the economics of recession, with "defensive Keynesianism," or the economics of stability within a boom.

At this moment, I am noticing the return of a very familiar name, Wassily Leontief. Leontief is a deeply important figure to me. His work was critical to figures in my book, and I used his personal archives extensively. I think that as Carter did a great job of writing about Keynes, someone will have to do a similar biography of Leontief. If I am honest, I would like to be that person. If, as Carter points out, Keynes is worried about the politics of the stability and a society where one can have the option to be a middle-class person pursuing non-economic, artistic interests, I think Leontief is interested in resilience. His approach to the economy is to understand how it works on a technological level and to build policies that allow us to get past the road bumps presented by rapid change. I think a quote from a 1974 interview sums up his view of the role of economics and the economist well.

*The market is indeed a marvelous machine. It operates like a large automatic computer. As contrasted with amateurs who have only discussed them, anybody who has had practical experience with large automatic computers knows that these complex mechanisms break down a couple of times a day and that you must have repairmen standing around all the time fixing up this and fixing up that.

The idea that you can feed a problem into the computer at five o'clock in the afternoon before going home and find the answer neatly printed out in the morning is quite incorrect. Experience with automatic computers shows that you cannot rely on them to solve all your problems automatically. By the same token, you cannot rely on the competitive economic system to solve all your problems automatically either. You need a very large crew of troubleshooters on a standby basis. And mind you, a repair crew must know exactly how an engine is constructed and how it operates.

Now this is much more than a superficial analogy. Many proponents of the "competitive solution" of all economic problems are as naIve as those who assume that if you can get hold of an automatic computer, you can rely on it without any knowledge of what goes on behind those whirling discs inside.*

Beyond its politics, I think this quote describes features of Leontief's economics quite well. I will use the rest of this post to give some initial thoughts about these features and what they imply about a potential Leontief revival.

First, you can see that Leontief is indeed a planning theorist, but he is also relatively blase about capitalism. Ninety-nine percent of the time, a market solution might be quite easy to implement. However, in many cases – especially in a complex system undergoing technical and social change – the information mechanism breaks down, and there needs to be a method and bureaucracy to prevent problems before they arise. In the 1970s, Leontief noted that a planning board would not get us through the problems of stagflation immediately, but that was not its role. It was to warn relevant parties about possible bottlenecks that might cause such a rise in prices in the first place.

This concern reveals some deep roots in his thinking. Leontief was a Russian economist born in St. Petersburg. As a young man, he left the USSR due to political differences with the Bolshevik authorities over academic freedom and the case of his professor, Pritym Sorokin. In that Russian tradition, we can locate Leontief's thinking within the so-called "Legal Marxists." Legal Marxists were both a political and economic school of thought. Politically, they were Marxists in the sense that they believed that Marx's analysis of the stages of development was important to Russia. They used Marx to argue against agrarian socialists who thought that Imperial Russia could have a peasant revolution that would allow it to skip over capitalist development and go straight to socialism. However, these figures were not revolutionaries as they thought Russia had to become a capitalist economy first.

Moreover, their experience in an emerging economy led them to have a very unique and, I would say, important economic approach. Legal Marxists like Petr Struve and, most importantly for economic theory, Mikhail Tugan-Baranowsky were trained both in Marxism and Austrian Marginalism. Tugan-Baranowsky's intellectual project was to figure out how to make the labor theory of value work with the critique of it presented by Bohm-Bawerk and his concept of "roundaboutness" – or how capital goods produce other capital goods and also consumer goods. In Bohm-Bawerk's critique of Marx, roundaboutness means that it is the particular time in production, not labor exploitation is where capitalists derive their value added. Tugan-Baranowski and other Russian legal Marxists ( I should note here that Russian is a difficult identity Tugan-Baranowski was a Ukrainian and later was the finance minister of the social-democratic Ukrainian 1917 Central Rada which, shortly after his death, became the government of the Ukrainian People's Republic) noted that you could make the labor theory of value work together with roundaboutness if you reject, as Marx began to in Volume 3 of Kapital, that the rate of profit must fall. Instead, capitalists can change the technical composition of capital to create more or less roundaboutness from production to consumer goods output and maintain profits.

The falling rate of profit thus became a special condition to be created by very rapid innovation and growth, not a hard and fast rule. Capitalism could just go on and be relatively stagnant and stable. This inspired several further developments in Russian economic thought. First, it was behind Kondratieff's technological cycles, which showed how capitalist economies could adapt to productivity shocks created by new technologies without collapsing due to class conflict. It also was the impetus behind Ladislaus Bortkiewicz's (another Russian-born economist but not of Russian but Polish origin) solution to Marx's transformation problem. Bortkiewicz showed that you could get an accurate price and profit rates using a labor theory of value if you modified Marx in two ways. First, you solved the problem simultaneously rather than sequentially as a series of simultaneous equations. Second, you assumed a three-sector model wherein you have sectors which produce both machine tools, wage goods, and luxury goods.

Leonteif was closely connected to these figures. He was trained in St. Petersburg by Kondratieff and, after his move to Germany, completed his Ph.D. under Bortkiewitz. You can see a lot of that heritage in Leonteif's approach to economics. The Input-Output method has the reputation of being empirical rather than theoretical but that's not really the case. Leonteif was never very friendly to institutionalists like Wesley Claire Mitchell and agreed that pure emperical stastical testing was not very useful to an economic theory.

However, the input output method itself is designed to add some illustration to intersectoral ties of the kind that were so central to the Legal Marxists. One of the ways we can see that heritage is through the centrality of technology to Leontief models. Leontief solves his model by assuming a static production function. In other words, unlike other econometric models, labor and capital don't act like perfect substitutes at the aggregate because each sector has a different coefficient that is in fixed proportions and can only shift through technical progress of different production choices. Such a change has remifications through the model. Leontief I-O models are thus comparative statics at all times.

The technical implications of this are pretty cool as well. As a very interesting article in History of Political Economy explains Leontief never believed in any kind of automatic supply and demand co-determination. His first publication caused a debate with father of econometrics Ragnar Firsch because Leontief published on a method to determine supply and demand elasticities as separate functions. In his further development, Leontief rejected simultanous equation approaches like the ones that came from Firsch's research program through Haavelmo and Larry Klein and the Cowles Commission tradition. The latter group believed that models could only be fit in the reduced form; the fully solved system of equations in which all endogenous variables are functions of exogenous variables. In mathematical terms, that means reducing a matrix of endogenous variables – the structural form – into a vector that, as a linear structure, can be estimated using a least squares method of regression. Leontief's models stayed at the structural level, meaning they relied on matrix inversions to inform inter-industry ties that supplied final demand. However, crucially, that meant that the only way to test a model was through surveying specific production functions since linear methods obscured the real functioning of technology.

I am laying out some of this technical background because I think it says a lot about the Legal Marxist heritage and its political implication. The Legal Marxists weren't revolutionaries. They were left-liberals and social democrats who believed that capitalism was with us for a very long time. Turgan-Baranowski's politics and argument for economic planning was not Marxian but Kantian. I think Leontief has the same political valience. He is about managing the imperfect system called captialism toward some political values. Unlike Oscar Lange or even Walras, his mathematical model of socialism did not assume that socialism could create the perfect price signal. Rather, that socialism, or at least social progress, meant accepting the imperfection of price signals and supplementing them.

On the other hand, this means Leontief's system has a hole in it that is political. How does a society set a general goal and who gets to do it? Moreover, while the rate of profit exists in the background of Turgan-Baranowski and Kondratieff, it has more or less fallen away in Leontief. In this regard, while Leontief's economics is very structural, it actually doesn't say much about the kinds of productive structures that Means' attempts to find inter-industry dependencies were concerned with. My still only half developed theory is that the I-O matrix is a comparative static isn't just a technical feature. It is a reflection of Leontief's lack of a political theory of change in the economy. A theory that I think sunk a lot of his efforts to create a more humane planning in the 1970s.

However, that does not mean he is useless. Leontief methods are a big part of how we understand the economy to this day. They simply work better than many other emperical, econometric models because they are grounded in concrete realities of technical processes rather than assumptions about substituabilites. However, to really fulfill what Leontief wanted them to do – to help with the process of learning-by-monitoring they need to be put into a broader, politically embedded system of both data gathering and decision making. For that, we need other forms of governance models and mechanisms.

On the last part, stay tuned because some colleagues and I are writing a grant to look into how we can bring together Leontief with Keynes through uncertainty decision making models. But that is for another time... That said, with our growing concern about supply chain stability, the structural causes of price movements, and generally understanding the real economy, Leontief is going to have a big revival.